Introduction

From early childhood, I recall being filled with wonder as my older brother, John, talked about his school field trips to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in 1957 and 1958.

It took me nearly fifty years to get to Malheur, where I was deeply impressed by the birds and the quiet, natural soundscape.

The impression of the east side of the Cascade mountain range that has stuck with me is a high desert dominated by sagebrush and juniper trees. In spring, after about a two-hour drive from Bend on Highway 20, you come to the small towns of Burns and Hines. You will find lush green fields flooded with water in good snow years. This is the entry point to the Malheur-Steens complex, the traditional home of the Northern Paiute people for more than nine thousand years. 1

The is no other place in the Northwest, and few anywhere, like the Malheur-Steens complex. The ultimate pilgrimage for Oregon birders and one that is immensely satisfying for anyone interested in the natural world, Malheur National Wildlife Refuge lies at four thousand feet in the high desert at the northern end of the Great Basin. The Great Basin is sometimes thought of as an empty place, even a sterile place. The desert is neither empty nor sterile; indeed, it is full of life adapted to its requirements. Malheur, though, provides that astonishing change agent: water. In some years there isn’t much; in other years there is too much. 2

In the mid-19th century, homesteaders and ranchers moved into the area. Near the end of the 19th century, poachers killed nearly all the Great Egrets around Malheur Lake for the fashion industry. Ten years later, in 1908, the photographers William L. Finley and Herman T. Bohlman made their first visit and documented the devastation, enabling them to convince President Theodore Roosevelt to set aside Malheur and the Lower Klamath-Tule Lake areas as wildlife refuges. More recently, naturalists, birders, and adventurers have been drawn to the remote natural wonders of the Malheur-Steens complex.

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, situated in remote Harney County in southeastern Oregon, is a birding hotspot that became more widely known during the infamous 2016 armed takeover. 3

A group of armed men, primarily from outside Oregon, took over the headquarters of the Malheur Refuge in January 2016, urging the citizens of Harney County to join them in a Sagebrush Rebellion against Federal control of public lands.

The worst-case scenarios did not come to pass, and, two years later, life in Burns and Harney Country had mostly returned to normal. In 2017 and early 2018, Harney County citizens were as busy as ever—or more so—working together to plan how to resolve natural resource problems through peaceful, collaborative means. Having received an explicit invitation, backed by force, to host a new, heavily armed Sagebrush Rebellion, the community had declined it and returned to its proven collaborative methods. Harney County chose sagebrush collaboration. 4

Water Levels at Malheur

The rivers and lakes in the Malheur-Steens complex do not flow to the ocean but ultimately evaporate or flow underground. 5

Malheur Lake is fed by the Donner und Blitzen River (the Blitzen River), flowing from Steens Mountain to the southeast and the Silvies River from the Blue Mountains to the north.

There was so little water the last two years, as in the 2023 photo below, that I didn’t intend to stop this May at “The Narrows,” a bridge between Malheur Lake and Mud Lake. As we neared the pullout, however, I saw, to my surprise, an expanse of water under the bridge, so I turned off to capture the above photo.

Later in the week, the clouds’ reflections above Malheur Lake were a visual feast to savor (see the photo at the top of the article).

A friendly volunteer at the Refuge bookstore explained that the amount of water in the Malheur basin this spring appears to be the most since 2012. 6

Water is critical to the migratory birds that use Malheur as a stopover, as noted in the executive summary of the Refuge’s Comprehensive Conservation Plan:

The Refuge is famous for its spectacular concentrations of wildlife which are attracted to the Refuge’s habitats and abundant water resources in an otherwise arid landscape. 7

We were surprised at the number of White-faced Ibis (Plegadis chihi) we saw in Malheur on this trip. The abundant water was probably a key reason. I learned more about how vital water is to Ibis by referring to a report prepared by a team of researchers from the University of Montana and the Intermountain West Joint Venture on how important Ibis is as an indicator species for the health of the wetlands in the arid west.

White-faced ibis (Plegadis chihi), a wading bird reliant on wetlands throughout its annual cycle, serves a key role in marking ecologically valuable wetland systems on both public and private land. In the West, ibis breed and forage exclusively in wetlands. The birds rely on both deep water habitats and shallow temporary wetlands, including agricultural fields. This means they require high wetland diversity to support the energetic demands of raising offspring and daily migrations between nesting and foraging locations. Because their reliance on spatially broad and diverse wetlands aligns with the needs of other wetland-dependent wildlife, ibis are a useful umbrella species for wetland diversity and function. 8

The Ibis above flew low over the marshland around the Buena Vista Ponds as I leaned against our car to steady the camera against a strong wind.

A Rolling Photography Blind

Some of the most reliable areas to see shorebirds are on the dusty gravel roads connecting private ranches on the northern edge of the Refuge. The car was a rolling blind for photographing birds that would fly if we opened our doors.

I spotted this Sage Thrasher (Oreoscaptes montanus) while rolling slowly along Ruh-Red Road. As the common name indicates, Sage Thrashers depend on sagebrush habitat for survival. 9 This was my first time seeing a Sage Thrasher, but I likely heard their long and melodiously jumbled song on early mornings at Malheur. Click here to listen to the beautiful song of the Sage Thrasher.

Also, in the dry habitat, Hideko spotted and photographed a Willet (Tringa semipalmata), “the only North American sandpiper with a breeding range that extends south of the North-temperate region,” to as far south as Venezuela. 10

The wetlands along Lawen Lane provide excellent habitat for Long-billed Curlews (Numenius americanus). On our last day in the refuge, we spotted at least one walking through the tall grass.

In the spring of 2019 we had a closer view of a Long-billed Curlew and a juvenile in the tall grass; you can also hear the distinct call of these large shorebirds in the video clip I captured at the scene. https://vimeo.com/358202926?share=copy

Hideko captured a clear view of a Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) in the wetlands along Lawen Lane. The range of behaviors of the beautiful shorebird is nicely captured in the paragraph below from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

The Black-necked Stilt is a study in contrasts. Its shiny black wings and back oppose the white breast, and both are accentuated by long, bright red legs. Undisturbed, stilts wade through shallow wetlands and flooded fields with a careful grace. When disturbed during the breeding season, however, all semblance of grace disappears. Agitated stilts yap incessantly, dive at predators, and feign mortal injuries. After a day of field work near breeding stilts, the yapping echoes in one’s head until the next morning when the sound is renewed by the continuing calls of vigilant parents. 11

Despite the abundant water, we only saw one American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) on the trip. We usually see them together with Black-necked Stilts at Malheur and Klamath Basin, so it was disappointing that we didn’t see more Avocets this time. The photo above is from our 2011 Malheur visit.

American Avocets are not listed as endangered, but little is known about their migration patterns, such as where they spend the winter. 12

Steens Mt Road

From the Buena Vista Overlook, perched on rimrock 17 miles south of The Narrows, you can see Steens Mountain to the southeast, including the distinctive notch in the wall of Kiger Gorge.

For someone who never leaves the Blitzen Valley during a visit to Malheur, Steens Mountain can appear to be simply a backdrop, more interesting than sky but basically just painted onto the cloud-flow. 13

Snowmelt from Steens Mountain is the source of water for the Blitzen River that runs through Malheur.

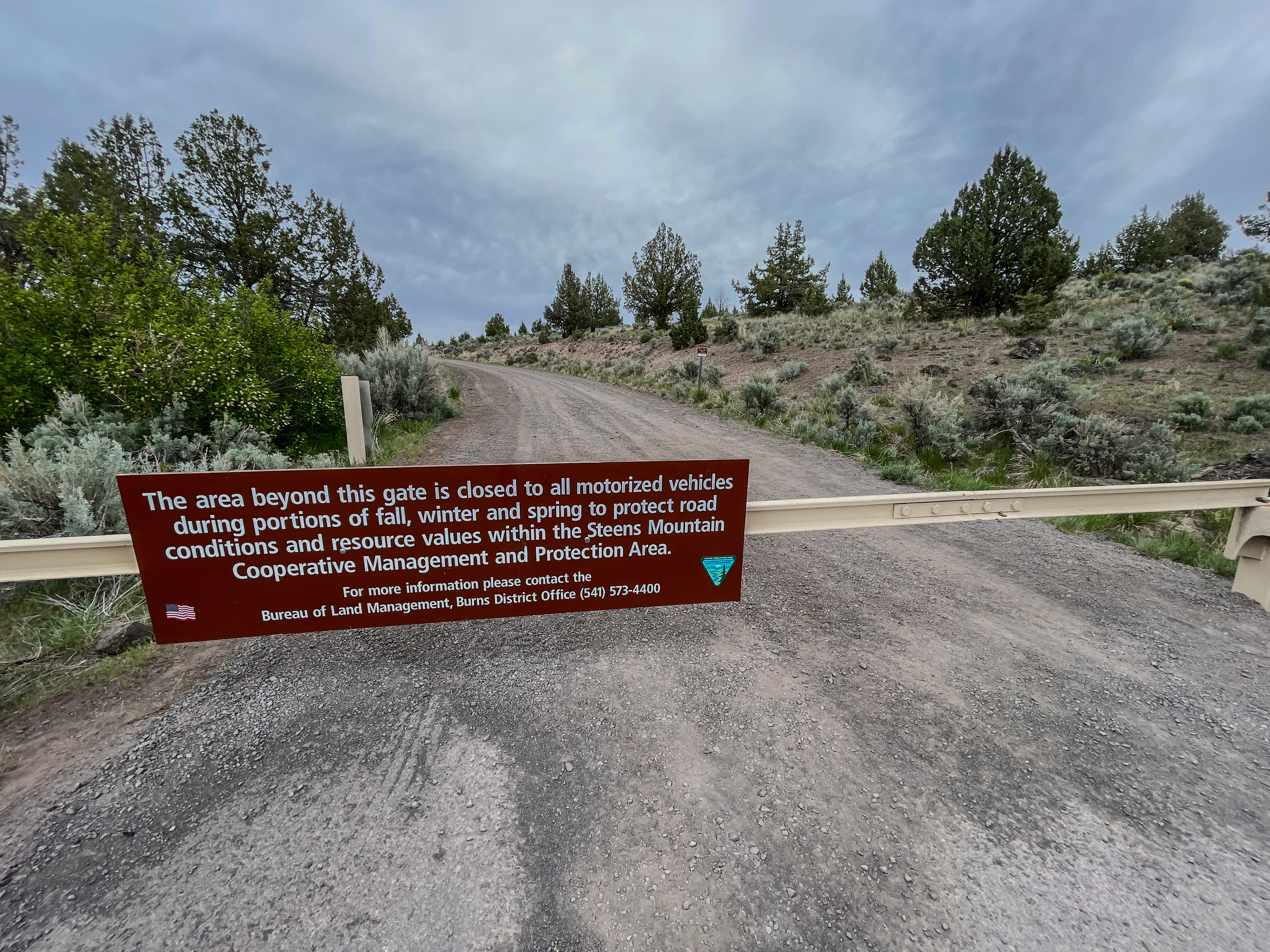

The Steens Mountain Road begins at Frenchglen and is an adventure not to be taken lightly. It is closed during the winter at a gate at Page Springs Campground and usually opens in July after the snow has been cleared from the road at higher elevations. Before starting from Frenchglen, it is essential to have a full tank of gas, sturdy tires, and good ground clearance on your car, as there is no gas available on the road and no cellphone coverage.

The grade of the Steens Mountain Road is gradual for the first several miles as it winds through open sagebrush country up the mountain’s west side. In June 2019, the road was open partway, while work crews continued clearing snow at higher elevations.

To get a fuller sense of this region, it is vital to explore Steens Mountain, the source of much of the water, but driving the Steens Mountain Road on a spring trip is impossible. Accordingly, we will shift seasons from spring to fall in the text and photos below.

Nearly every tilted fault block mountain in Oregon has its steep face toward the west—these mountains did not have glaciers. But Steens Mountain has its steep face to the east and a long gentle slope that rises up from Frenchglen (elevation 4,184 feet) more than a vertical mile to the crest at 9,670 feet. 14

About 20 miles after passing the snow gate at Page Springs, you arrive at the Kiger Gorge Overlook, a spectacular vantage point over this glacier-carved valley. Alan Contreras provides a memorable description of the experience of standing at this spot.

Kiger Gorge itself is perhaps the greatest visual wonder on the mountain. Completely invisible from the west unless you realize what lies below the mountain’s northwestern rim, it is a glacially scooped valley with a creek and aspen along the bottom, but from the overlook at its head, the aspen and everything below has a toylike, miniaturized quality because it is fifteen hundred feet below at the headwall and extends into the far distance before curving slightly to the west. If there are no tourists around, you can hear a low purr from the gorge, the distant sound of the creek and the wind in the aspen, with the occasional croak of a raven drifting across the canyon. 15

There is one section of the Steens Mountain Road where I remember driving on a knife-edge, with steep drop-offs on both sides, but I couldn’t remember exactly where this was, nor if my memory was correct. Alan Contreras confirms the location was just before the East Rim Overlook: “a hogback ridge of rock a hundred yards wide that drops off of about two thousand feet to the west and five thousand feet on the east.” 16

The East Rim Overlook presents a breathtaking view of the Alvord Basin far below, described below by Alan St John.

To the east, directly below, you can survey the entirety of the Alvord Basin, north to south. This huge trough once held an Ice Age lake, but a 10,000-year-long climatic shift toward greater aridity has dramatically changed the scenery. Through binoculars and heat waves, you can see brushy sand dunes along the edges of white alkali flats in the barren Alvord Desert. 17

The Big Indian Gorge Overlook is on the rougher southern end of Steens Mountain Road. A 17-mile round-trip trail runs along the gorge’s floor, which I have yet to hike.

The Malheur-Steens area offers much more to see, including the mountain’s east side and the Alvord Desert.

Unforgettable

I am grateful that my brother sparked my curiosity with his stories about the Malheur Wildlife Refuge all those years ago and that I have been able to explore this unique environment myself.

The remote location, the habitat mix of sagebrush and juniper next to wetlands, the changing water levels from year to year, the wide variety of plants and animals, the prominent songs and calls of migratory birds against the utterly quiet background, the dark night skies, and the rugged beauty of the fault block of Steens Mountain are unforgettable.

My experience with Malheur was complicated and interrupted by the armed takeover of the Refuge Headquarters in 2016. Still, as I read more about the community’s resilience and spirit of collaboration, I have a sense of cautious optimism for the future.

On May 2017, our first visit to Malheur Refuge, following the end of the occupation, I made the following notes in my journal about the birds we saw there.

Today, we visited Malheur NWR, and were delighted to see the visitor center open (since late April), and it was looking very good, with some upgrades to facilities (e.g., restrooms). We saw quite a few birds and got some photographs: western tanagers, yellow-headed blackbirds, white-faced ibis, great horned owl, brown-headed cowbirds, black-necked stilts, avocets, bald eagle, northern harriers, yellow warblers(?), bonaparte’s gulls [probably Franklin’s gulls], red-winged (tri-colored?) blackbirds; white pelicans. I forgot to include: cinnamon teal, shovelers, and mallards.

I urge readers who haven’t experienced the Malheur-Steens region to visit and see for themselves. I think you, too, will find this remote part of the Great Basin unforgettable.

- Malheur’s Legacy: Celebrating A Century of Conservation 1908 – 2008, p. 11. ↩

- Edge of Awe, Introduction by Alan L. Contreras, p. xxi. ↩

- Click on the link below to see a map of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service https://www.fws.gov/refuge/malheur/map ↩

- Sagebrush Collaboration, Peter Walker, p. xiii-xiv. ↩

- Wikipedia: Great Basin ↩

- I have not been able to find annual data on the water levels at Malheur Lake. ↩

- Malheur National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan, 2013, Executive Summary, ES-i.) ↩

- “White-faced Ibis and Water in the West: Indicating the Path to Resilency in an Arid Region”, Shea Coons, University of Montana in Intermountain Insights, Intermountain West Joint Venture, p. 1. ↩

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Birds of the World birdsoftheworld.org (paywall). ↩

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Birds of the World birdsoftheworld.org (paywall). ↩

- Cornell University Lab of Ornithology, Birds of the World birdsoftheworld.com (paywall) ↩

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Birds of the World, birdsoftheworld.org (paywall). ↩

- Afield: Forty Years of Birding the American West, Alan Contreras, p. 54. ↩

- Atlas of Oregon, William G. Loy, Stuart Allan, Aileen R. Buckley, James E. Meacham, Second Edition, p. 129. ↩

- Afield: Forty Years of Birding the American West, Alan Contreras, p. 58. ↩

- Afield: Forty Years of Birding the American West, Alan Contreras, p. 58. ↩

- Oregon’s Dry Side: Exploring East of the Cascade Crest, Alan D. St. John, p. 203. ↩